“Not many people know these are here.”

A cheerful employee of PoshPetCare is ushering me past two metal gates into her place of business’s forecourt. It’s March 2018, and I have been skulking around the dinky, house-like building on Hollywood’s Sunset Strip. The staffer has caught me standing on tippy-tippy-toe on the sidewalk outside, trying to take photos over a wall of imposingly tall shrubbery. Rather than telling me to scram, she’s being unexpectedly helpful.

Once inside, I’m free to roam about shooting pictures of the pavement in front of the pet-grooming shop. More specifically, I can document the 30 circular cement discs embedded there. Each is signed, usually with a date in the early 1960s and indentations where signatories had left prints of their elbows.

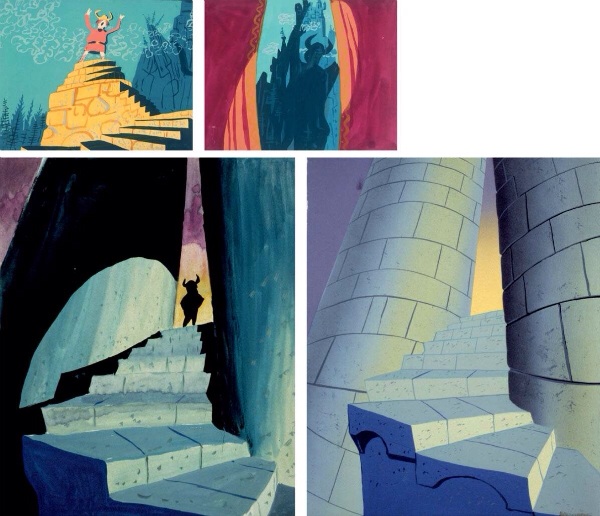

By now, you’re mystified—unless you’re a particularly serious Rocky and Bullwinkle fan. In that case, you may know that PoshPetCare’s home at 8218 Sunset Boulevard was once the headquarters of Jay Ward Productions, the cartoon studio that brought us the moose and squirrel’s adventures beginning in 1959. Back in the day, the dated signatures and elbow prints were accompanied by a statue of Bullwinkle hoisting Rocky on his left arm, which studio founder Jay Ward had commissioned in the fall of 1961 when The Bullwinkle Show came to prime-time TV. You didn’t need to be a Bullwinkle scholar to know about this statue, since it was readily visible from the street and stood for decades.